Tawny Mole Cricket (Neoscapteriscus vicinus)

Detailing the physical features, habits, territorial reach and other identifying qualities of the Tawny Mole Cricket

Note: The above text is EXCLUSIVE to the site www.InsectIdentification.org. It is the product of hours of research and work made possible with the help of contributors, educators, and topic specialists. If you happen upon this text anywhere else on the internet or in print, please let us know at InsectIdentification AT gmail DOT com so that we may take appropriate action against the offender / offending site and continue to protect this original work.

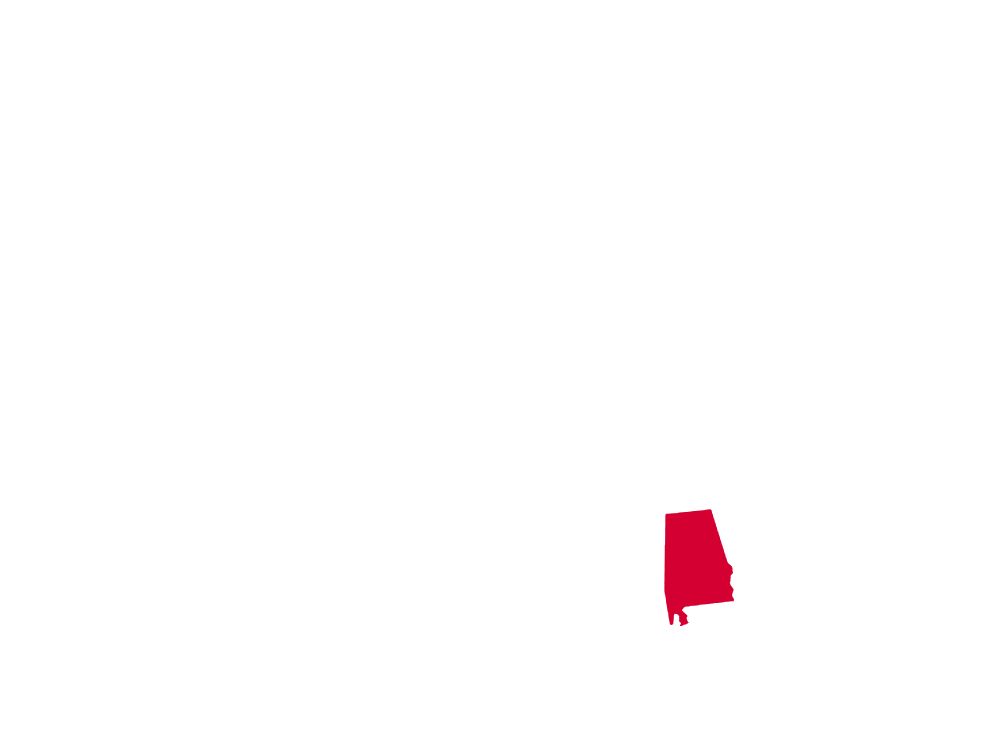

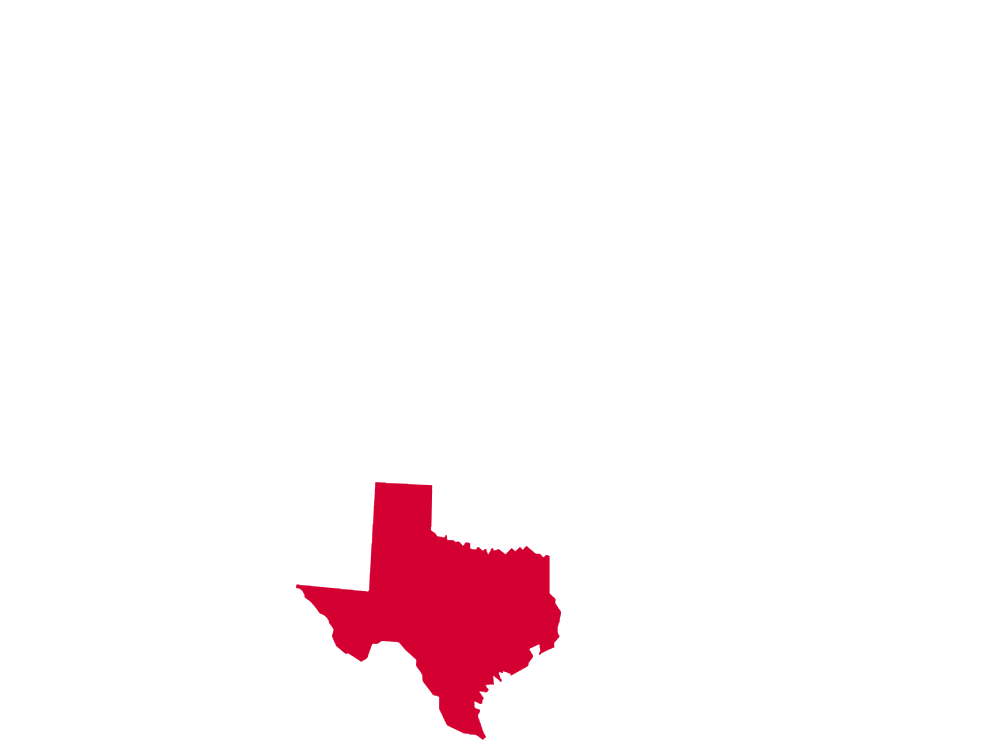

* MAP NOTES: The territorial heat map above showcases (in red) the states and territories of North America where the Tawny Mole Cricket may be found (but is not limited to). This sort of data is useful when attempting to see concentrations of particular species across the continent as well as revealing possible migratory patterns over a species' given lifespan. Some insects are naturally confined by environment, weather, mating habits, food resources and the like while others see widespread expansion across most, or all, of North America. States/Territories shown above are a general indicator of areas inhabited by the Tawny Mole Cricket. Insects generally go where they please, typically driven by diet, environmental changes, and / or mating habits.

Colors: brown

Colors: brown